Yesterday’s News Remembering Our Forgotten Past April 2024

Daniel Oliver in the Civil War

Franklin County and the town of Chambersburg were unique for their involvement in the civil war and experienced more military activity than any other area in the North. Its location in the Cumberland Valley made it the target of three major Confederate raids, and a full invasion in the Confederate campaign of 1863 that culminated in the battle of Gettysburg. More than 150,000 soldiers from both sides camped in the countryside of Franklin County at various times during the war.

Of course, since we have few direct quotes from Daniel Oliver we cannot say what effect these events had on his young mind, but we do know that on February 3rd of 1864 he enlisted in the Union Army for a three-year stretch during a campaign for new recruits by the 21st Pennsylvania Cavalry (182 Regiment of Pennsylvania Volunteers). He Mustered in (showed up for roll call) on April 30, 1864. He was mustered out July 8, 1865 after the war had ended. In his enlistment documents he was described as having a dark complexion, brown hair and hazel eyes. He was five feet four inches tall.

It might seem to those of us unfamiliar with the Civil War that 1864 was late to join the army and that he might have missed the greater part of the action, but as it happens 1864 was the dramatic final phase of fighting that had been building since 1861. During those three years Lincoln had been trying to find a general who would confront Lee’s Army and destroy it, but until Gettysburg Lee had been too bold and the Union general’s too timid to make decisive difference in the resolution of the war. But in 1864 Lincoln had finally found Ulysses S. Grant who would soon confront Lee’s armies in the decisive battles of the Wilderness, Spotsylvania, and Cold Harbor. Battles that would follow at Petersburg, and Richmond, the Weldon Railroad, Poplar Springs Church, Bellefield, and others would lead to the Appomatox Campaign and Lee’s surrender at the Appomatox Courthouse.

The Twenty-first cavalry in its first incarnation was created during the months of July and August, 1863, nearly a year before Daniel joined. Its creation was the result of President Lincoln’s call of June 15, 1863 for cavalry for six months service. The companies that were formed were equipped and mounted at Camp Couch near Harrisburg, and then sent to boot camp near Chambersburg. In January of 1864 the units original enlistments were expiring and authority was given to reconstitute the regiment for three years service. In February 1864 its troops were concentrated at camp near Chambersburg where the troops who didn’t choose to re-enlist were mustered out (discharged from service). The remainder had their enlistment extended and its open slots filled by new recruits.

The unit initially trained at a camp about four miles from Chambersburg where they constantly drilled so that the troops could get used to their new role as soldiers. The men being so close to home were allowed to visit their homes often and for their families to visit the camp. March and April were busy with training. At the end of March the regiment attended a formal flag presentation to accept its regimental colors.

The unit left Chambersburg at 6 a.m. on the 16 of May and marched for four days to reach Camp Stoneman in the Capitol and shortly after arriving an order was issued requiring them to turn over their horses and equipment as they were to be outfitted as infantrymen. This was the result of a decision by the new commander of the army Ulysses S. Grant who wanted to take advantage of the numerical superiority of his army in his battle with Lee, but to do this he needed more infantry.

The men were not only wounded in their pride. Many lost a family assets as they had brought their own horse from home and it would never be returned. Only one company was spared this indignity, that was Company D, which had been singled out to be sent to Scranton to suppress protests by coal miners who objected to the draft. There were reports in the press at the time that the order to become infantry “caused much dissatisfaction among the officers and men who protest earnestly against it.”

The new infantry regiment was issued Springfield rifles, new cartridge and cap boxes, bayonets and other equipment for foot soldiers. The next day the new unit marched to Alexandria Virginia to travel down the Potomac River and Eventually to the Army of the Potomac.

Boats took the men to Port Royal, about a dozen miles below Fredericksburg on the Rappahannock River. The unit remained in Port Royal until May 31 when it marched south as a guard for 400 wagons reaching the Pamunky river that night. An order reached them on bivouac that assigned them to the Sweitzers Brigade, Griffin’s Division, Fifth Army Corps. The next morning they pressed ahead to join the Fifth Corps at the front near Cold Harbor. They arrived early in the afternoon of June 1st.

Prior to their arrival U.S. Grant’s new offensive against the Confederates had already begun with clashes at the Wilderness campaign, Spotsylvania Courthouse, North Anna River and Totopotomoy Creek.

In march of 1864 Ulysses S. Grant had been made Lieutenant General and put in charge of all Union armies. He immediately put a plan into motion that called for five union armies to move simultaneously on the south preventing them from reinforcing different areas from different times. Grant travelled with the Army of the Potomac led by General Meade. Beginning in May of 1864 the overland camp began which was intended to get between Lee and Richmond. They clashed at the Wilderness, Spotsylvania Courthouse, at North Anna River, and Totopotomoy creek and finally at Cold Harbor.

COLD HARBOR

Daniel’s first battle experience was likely in the fight for Cold Harbor on June 1 through June 7. It was a difficult way for the newly constructed infantry regiment to enter battle. The battle had been casually planned, the corps commanders had not prepared properly and the infantry regiment had not trained in infantry maneuvers.

On June 1st the regiment joined Sweitzer’s brigade, part of the Fifth Corps commanded by Major General Warren at Bethesda Church, near Old Cold Harbor, Virginia. The landscape featured heavily timbered areas mixed with dusty open fields, all interlaced with trenches and every kind of earthwork fortifications imaginable. The regiment, with the entire division, became part of the right flank near Bethesda Church. The plan had originally been that the three corps under Generals Hancock, Wright and Smith were going to attack that same day, but because of the long march and the fatigue among the troops the attack was postponed until the following day.

On Thursday, the third of June, the regiment was at Bethesda Church in close proximity to the enemy and engaged busily in throwing up defenses. While they were at this work the Confederates kept up an almost uninterrupted fire upon them, and among the casualties was Lieutenant Richard Waters hit by a shell fragment that tore through his neck. The men of Company E, including Daniel Oliver, were nearby when this occurred. Waters was the first commissioned officer of the 21st to be killed in action on only the second day at the front. Waters was only twenty-five and had been married in February. His body was returned to his home in Scotland, Pennsylvania, very near Daniel’s home in Smoketown.

The battle began early the next morning with the roar of artillery from the left around Cold Harbor. It was about 6 a.m. that attacks from the Bethesda Church sector moved forward. Sweitzer’s brigade began to move forward toward an old orchard which the enemy had used to establish his line in the edge of a wood. The men sought protection from fences, trees, and old outhouses in the clearing. The further the men went into the clearing the more they were exposed and soon enough they faced a storm of shell, grape, canister, and musket balls . The brigade creep turned into a run, driving the Confederate line forward, back toward their own fortifications.

But there was a price to this progress as men began to fall. Blacksmith Jacob Lear of Company M was hit in the left leg, the bullet shattering the bone. Sergeant Darling J. Vincent of Company C was hit in the hand and later died from complications. Corporal Wiliam H. Sutton was shot in the thigh. Daniel H. Ney of Company I was hit in the arm. Austin C. Eckley was shot in the face. Among the officers Captain William H. Phillips commanding Company G was wounded by a shell fragment and taken from the field. First Sergeant Emmett D. of Strasburg, Lancaster County, was shot in the mouth, knocking out all the teeth on the right side.

They finally reached a point where they had some protection from the enemies fortifications and the brigade struggled to reorganize. Colonel Boyd, the head of the regiment encouraged the men, sitting down and smoking a pipe as bullets “flew around him like pelting hail.” Then a bullet hit him in the neck, just missing his carotid artery, but lodging in a vertebra. He lost the use of his right arm and while continuing to give orders was taken from the field. Lieutenant Richard F. Moson took command

The brigade then came under crossfire because the division to their left faded under fire. The attack was eventually driven back, but while they were pinned down the men noticed fire coming from the upper story of a nearby barn. Colonel Sweitzer called the 5th Massachusetts artillery forward and, firing over the heads of the soldiers, one gun turned the barn to splinters on the third shot.

The soldiers remained in place the remainder of the day and Grant called off any new attacks. The regiment had lost eight men killed and forty-seven wounded. The entire brigade lost 216 men (killed, wounded, missing). In the attack more than six thousand Federal troops were killed, wounded or missing. Private Henry F. Charles wrote later, “Some of the dead were bloated so bad that buttons tore off their coats. All of us that had blankets took them to cover the dead next day and shoveled a little dirt over them and that is all the burial they got….”

The next day the 21st Pennsylvania Cavalry advanced toward the Shady Grove Road and found that the Confederates had left. For the next few days firing continued between the armies. During this period the wounded were stranded between the lines and many died there. Finally, the unit marched toward Cold Harbor which it reached at eight o’clock on the 6th. The soldiers set up camp and lounged the rest of the day. On June 7 they marched to the Chickahominy River and went to work fortifying the site. They remained there until June 12.

PETERSBURG

The battle for Cold Harbor behind them the 21st Pennsylvania would soon journey with the 5th Corps toward the city of Petersburg, about twenty-five miles south of the Confederate capital of Richmond as part of Grant’s plan to eventually take the city. The 21st was loaded into transports and crossed the James River near Wilcox’s Landing on June 16. From there it marched towards Petersburg past midnight.

Petersburg was surrounded by about 10 miles of field fortifications that the Union soldiers would have to breach in order to take the town. An earlier assault by General Smith’s men had captured about a mile of the outer fortifications, but found there was an inner fortification just as strong as the outer. Subsequent attacks were repulsed by General Pierre Beauregard, also know as “Little Napoleon.” On June 17 the Federal troops were reinforced and there was the expectation that the next day would bring a big breakthrough.

Throughout the afternoon of June 17, the 21st Pennsylvania Cavalry shifted southwest to extend the Union line between General Burnside’s Ninth Corps toward the Norfolk and Petersburg Railroad. Disrupting this railroad which supplied Richmond was one of the goals of the assault on Petersburg. On the way there they marched over the field where the second Corps had been engaged the day before, and the ground was covered with their dead.

The 21st Pennsylvania, the largest regiment in the brigade, reached their destination and were joined by two veteran regiments to the brigade, the 91st and the 155th Pennsylvania. An assault was expected that evening, but was delayed until early the next morning. When Sweitzer’s brigade advanced toward the enemy the men were surprised to find no resistance. They sent scouts ahead and found that General Beauregard had ordered his men to quietly withdraw under the cover of darkness to a more consolidated line of fortifications closer to the city of Petersburg. It was not until noon that the 21st Pennsylvania Cavalry under the command of Lieutenant Colonel Moson, finally advanced with bayonets fixed over the top of a hill descending into a ravine along the banks of Taylor’s Creek, directly below the enemy’s new line of defense. The force was met with a volley of musketry from the earthworks in front and above them. At least sixteen pieces of enemy artillery were trained on them. The regimental colors went down at least four times. Lieutenant Henry G. Lott of Gettysburg was shot in the head, twenty-six-year-old carpenter Lafayette Brenizer of Arendtsville was shot in the neck. Private Conrad Linn was shot through both legs. Regiment commander Lieutenant Colonel Moson was hit in the hand but remained on the field. Major Charles F. Gillies took over regimental command, but shortly afterwards he was shot in the leg. The regiment was pinned down about 150 yards from the enemy fortifications and gradually pulled back to a less exposed position. Some men fortified their position as other kept up a fire on the enemy. They remained under fire until the following morning when they were relieved. Attacks were made all along the line through the evening of June 18th but all failed to drive the Confederates from their position.

Another attempt was made on June 22nd. The 21st Pennsylvania Cavalry with the rest of Sweitzer’s brigade was moved to the left of the army’s line near Jerusalem Plank Road. They were operating to support Second Corps which was trying to flank the enemy out of their positions. This was unsuccessful and caused many more casualties.

After this the regiment was moved a few times, but without contact with the enemy. The difficult challenge during this time was enduring the weather and the environment. Temperatures were nearing 100 degrees and the ground was covered six-inches deep in a powdery dust, the result of long-standing dry conditions in the area. The landscape was desert-like as the breeze lifted the dust and limited visibility. As these conditions persisted the purpose of the army turned from a quick victory to a siege. The duty of the men turned toward digging trenches, improving roadways and constructing fortifications. On July 13, the regiment finally moved again to relieve the 155th Pennsylvania on the front line and remained there for eight days without significant incident. Afterward they returned to the rear and their manual labor.

The Burning of Chambersburg

Outside the confinement of army life other events would have an impact on the 21st Pennsylvania Cavalry. We don’t have good information on how much contact the troops had with events in the outside world, in other areas of the war or in civilian areas so we don’t know if they had contemporaneous knowledge of things happening back home. And the new events in Pennsylvania were, to say the least, dramatic.

In May of 1864 General U.S. Grant gave Major General David Hunter command of the forces in the Shenandoah Valley and ordered him to employ "scorched earth" tactics and disrupt any activity that could support the Confederate war effort. Hunter went beyond Grant’s orders and destroyed private homes and other properties that caused bitter resentment in the south.

As an act of reprisal Confederate General McCausland and three thousand troops were sent to Franklin County and threatened the town of Chambersburg with destruction. General McCausland rode up to a number of citizens in the town and told them that unless five hundred thousand dollars in greenbacks, or one hundred thousand dollars in gold was paid in half and hour, the town would be burned. The citizens and all their representatives refused even though a number of them were placed under arrest and were threatened with imprisonment at Richmond. Once the Confederates realized the ransom would not be paid they divided into squads and fired every other house. They entered every room in the houses to plunder for money and other treasures, then broke up the furniture in the main room, poured oil or other flammables on it, and lit it afire. No time was given to remove women or children or the sick. This continued for more than two hours and more than half the town was on fire. The damage amounted to some three millions of dollars and left homeless three thousand citizens. One of the buildings burned was the county courthouse which held all birth, marriage and death records.

At some point in the melee the written order to burn Chambersburg, signed by Confederate General Jubal A. Early, was shown to local attorney J.W. Douglas. When an Episcopal clergyman of Hagerstown was taken hostage and brought to General Early’s headquarters at Wiliamsport, the general informed him that he had directed Chambersburg to be burned in retaliation for the destruction of property in Virginia by Grant, Meade, and Hunter, and that the account was now squared.

You may assume that when these facts were known to men of the 21st Pennsylvania Cavalry they would not have agreed that the account was squared.

Burnside’s Bombing of the Confederate Fort.

On the same day that General McCausland entered Chambersburg to burn it there was an explosion on the Confederate line that marked one of the strangest attacks of the war and one that was witnessed by the men of the 21st Pennsylvania, fortunate not to be part of the attack, but to have a good vantage point to see the event.

The situation at Petersburg had deteriorated from an expectation of quick success to a stalemate that seemed to have no end. Various plans were put forward to breach the Confederate line. One of Burnside’s regiments was made up of miners from Pennsylvania. Some of these men suggested that a tunnel should be dug under the Confederate fort and explosives buried beneath it. The explosion would then open up an attack on the railroad lines at Petersburg. The plan finally reached Burnside who approved it and the digging began. The work started on the 25th of June and was completed on the 23rd of July. The cavity under the fort was filled with 8,000 pounds of black powder and daybreak on the 30th of July was set for the attack. Burnside’s forces were to dash through the breach and seize a crest known as Cemetery Hill a few hundred yards to the rear. Warren, to burnsides right was to join in the assault. While the assault had the greatest expectation of success everything went wrong. First the Fuse, once lit, had subsequently gone out. They waited an hour then two men volunteered to go into the mine. They found the break in the fuse and relighted it, emerging from the mine just as the explosion took place. A solid mass of earth mingled with timbers rose 200 feet into the air leaving a crater two hundred feet long, sixty feet wide and thirty feet deep where the fort had been. Guns from all the batteries opened fire.

Now the Union forces were urged to move into the crater and advance to the crest of the hill but the plan had not allowed for the easy entrance of the Union forces other than in the tunnel which could hold four or five abreast at most. The crater was also an obstacle, being steep on the sides and full of debris. The men who did manage to crawl out the other end were subject to murderous fire from the Confederates and most returned to the relative safety of the crater. Gradually it dawned on the commanders that the assault was failing and the men retreated over a period of time that cost many of them their lives as the Confederates direct mortar and rifle fire at the retreating men.

The Weldon Railroad

The 21st Pennsylvania Cavalry did not move again until August 15 when they were placed on reserve as the Ninth Corps moved to the front line. On the 18th the regiment marched toward the army’s left and covered about five miles along the Jerusalem Plank Road as they advanced through swamps of mud and knee deep water to reach the Weldon Railroad, a vital supply link that ran south from Petersburg to Weldon, and eventually to the Confederacy’s only remaining port, Wilmington, North Carolina. After the attrition of leadership in the 21st, Colonel Oliver Knowles returned from his staff position to take command. He ordered the regiment to begin destroying the tracks and telegraph lines around Wilmington. The regiment enthusiastically performed their task of destruction, shouting “Remember Chambersburg!” as they did so. After destroying several miles of track they began to prepare fortifications as they were near the enemy lines. At about noon on the 18th a heavy rain began and shortly afterward the Confederates attacked, led by Major General Henry Heth. The Federals and Confederates contested the control of the rail line for several days, the lines moving back and forth with the Union still holding the railroad.

On August 27th, the regiment was pulled off the line and spent September in routine duties and the occasional digging of fortifications and trenches.

Pottsville Riots

Back home in Pennsylvania one of the companies of the 21st Pennsylvania became involved in suppressing the draft riots that were features of the area around Pottsville, Pa. Company D of the 21st was the only company that had retained its character as a cavalry unit when it was separated from the regiment and sent to the Scranton area to help contain discontent over the war and the draft. A group of Democrats called “Democracy of Schuylkill County” held a large gathering on September 17, 1864 that lasted for four hours. As the meeting ended and people began to leave a party of twenty cavalrymen from Company D with drawn sabres rushed out of a side street and attacked people in the crowd. The soldiers went into the crowd cutting and slashing and when the people realized what was happening they hurled stones and clubs at the troopers. As they were outnumbered, the soldiers retreated and left the scene.

Several of the civilians were wounded but no one was killed. One of the injured was a Union veteran who had just returned home after serving three years. That evening the group recommended that Democrats attending meetings should come armed. This type of social unrest as the fall presidential election neared increased the possibility that Presidential candidate George McClellan would win the election and make peace with the South.

Battle of Poplars Farm

The Fifth Corps was reorganized in September and on the 24th the 21st Pennsylvania Cavalry (dismounted) was brigaded with Colonel Horatio G. Sickel’s new 198th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry from Philadelphia that was two weeks old. Six days later the new brigade marched west along Poplar Springs Road as part of an operation by Grant to attack Lee’s flank. The troops were ordered to hide in a belt of woods under enemy artillery that had little effect. When they were ordered to move the leadership of the 198th misunderstood its orders and was in the wrong position. Once the unit position was corrected they joined a wave of Federal troops crossing Squirrel Level Road toward Peebles Farm. The enemy troop they faced belonged to the division commanded by Robert E. Lee’s son W.H.F. “Rooney” Lee. The Federal attack overran the Confederate fortification, driving the enemy troops back toward the Boydton Plank Road, the route to the South Side Railroad.

The Fifth Corp commander General G.K. Warren that night said, “The Fifth Corps has done splendidly; principally Griffin,” which included the 21st Pennsylvania Cavalry. One man from the regiment was killed and nine others wounded in what became known as the Battle of Peebles Farm.

The Return of the Cavalry

One day after that battle the 21st Pennsylvania Cavalry was separated from the Fifth Corps and ordered away from the front. They were marched to Giesboro, just south of Washington, D.C., the Union army’s large central remount camp. After five months serving as infantry the 21st Cavalry was going to be given mounts and returned to service as a proper cavalry unit.

It took two weeks to get the regiment mounted with “good” horses. After being once again provisioned as cavalry the regiment was returned to the front and under Major Oliver Knowles was sent to the Weldon Railroad. They were ordered to join the Third Brigade of the Second Cavalry Division which included veteran units the 1st Maine and the 6th Ohio Cavalry.

As the election neared the leadership of the Union cause was skeptical about any risky battles that could discourage the public and affect the outcome of the election in favor of the anti-war sentiment. In the face of this resistance to aggression in the field Grant believed that success at Petersburg after the long siege would be a positive influence on public opinion. Thus, he decided to make another attempt at cutting the South Side Railroad. This sixth offensive at Petersburg was set in motion by an order from Grant and Meade which said, “Make preparations to march out on an early hour on the 27th to gain possession of the South Side Railroad, and to hold it and fortify it back to your present left. In commencing your advance, move in three columns.”

The cavalry under General Gregg was to move as part of General Winfield S. Hancock’s Second Corps. The entire force was to move before four a.m. on the 27th on the road leading from the Weldon railroad to the crossing of Rowantry Creek below Arthur’s Swamp across the Quaker road, and following this to the Boydton plan road.

Before reaching the Quaker Road the column met the enemy at the Hargrave farm. The enemy was behind fortifications and commander of the Brigade Colonel Charles Smith ordered parts of the 1st Maine and 6th Ohio to dismount with the 21st Pennsylvania remaining on horseback. They were ordered to advance and met little resistance as the Confederates fled across Rowentry Creek. When the brigade met the enemy in force they continued the attack and forced the enemy from their position of strength. Once the enemy realized the 2nd Corps was on the right they fled south.

Progress, however, was short-lived. A Confederate counter-attack dislodged 2nd Corps positions and left Gregg’s brigade open to attack from the rear. At the end of the day Gregg ordered his division to retrace the morning route which took them back to Perkins House at seven o’clock on the morning of October 28th. The regiment suffered the loss of eight men killed or died of wounds, thirty-two wounded and three who were wounded, but never found.

Lincoln Re-elected

In the election of November 8, 1864 Lincoln was victorious over his former General George McClellan which was critical to the war effort as the Democrat McClellan was bound by the party’s platform that pledged immediate peace talks with the Confederacy had he won. Lincoln’s election assured the troops that the war would continue to its end on the battlefield.

The Railroad Battle Continues

Great interest in the outcome of the election did not alter the military situation for the regiment and other elements of the Union army. The day before the election the regiment moved with the rest of the brigade to scout the Weldon Railroad six miles beyond Ream’s Station to Stony Creek. During this reconnaissance mission General Gregg learned that the enemy planned to build a branch line from the Weldon Railroad to the Southside Railroad, reestablishing a continuous rail line into Petersburg. This new information gave rise to a mission of damaging more of the Confederacy’s rail lines. On December 7 the division moved toward the Weldon Railroad with the purpose of destroying more distant sections. The army destroyed the Nottoway railroad bridge on the morning of December 8. They continued down the Halifax Road, followed by Fifth Corps infantry, and started destroying a one-mile section of the Weldon Railroad. As fast as the road was torn up the ties were piled up and fired, and the rails place on top in order to bend them and render them unfit for future use.

The next day as they headed home from their mission Smith’s brigade was chosen to serve as rearguard with particular responsibility given to the 21st Pennsylvania. On December 10 the brigade began to return to base as snow fell. They went a short distance before the Confederate cavalry attacked. The 21st Pennsylvania kept the attackers at bay for several miles as the column retreated. The men of the 21st got across the bridge at Three Creeks and then tore it up to slow the Confederates. After a time the Confederates broke off their attack, but not before three of the 21st Pennsylvania Cavalry were killed and six were wounded.

The mission succeeded in destroying twenty miles of track and prevented the Confederacy from building a branch line to assist the Confederate troops besieged at Petersburg.

The Last Campaign

The war was proceeding apace toward what now seemed inevitable: the victory of the North over the South. At Nashville General George H. Thomas defeated Confederate General John Bell Hood’s Army of the Tennessee. On December 21, 1864 General William Tecumseh Sherman, completed his March to the Sea and Captured the city of Savanna, Georgia.

For the Regiment the successful raid on Belfield was their last field operation for awhile as the armies built winter quarters. The men were occasionally rotated into the front lines which now and then brought them under fire. Many of the men applied for leaves of absence to visit loved ones and families visited the regiment on bivouac. There was some reorganization of the regiment in the new year with Major Oliver Knowles being promoted to colonel and sent to command the Third Brigade while its commander was on leave. Major Bell commanded the regiment during this time. Company D which had been on duty in the Scranton area since April of 1864 rejoined the regiment at Petersburg. Daniel Oliver’s Company E was detached from the regiment to serve with Sixth Corps headquarters, where it would remain through February. While there were occasional operations during February most of them brought little result and only low-level conflict. March, too, was mainly spent in waiting.

On March 29th General Phil Sheridan had command of all the army’s cavalry and his horsemen started out at six a.m. toward the enemy flank in the vicinity of Dinwiddie Court House. They struck enemy pickets near the small hamlet and drove them north. The 21st Pennsylvania captured two officers and nine men.

After this action the regiment remained in camp until March 31st. That morning two brigades of the Division were attacked north of the courthouse. The brigade was called to support their fellows and advanced toward the heaviest firing, but the 21st Pennsylvania missed the fight since it was on picket duty south of Dinwiddie and rejoined the brigade that evening. In the next days the 21st saw little action, but cheered when they heard on April 1st the Federal infantry broke the enemy lines southwest of Petersburg. They heard that many Confederates were giving up as they concluded that their cause was lost.

The brigade march two days, April 3rd and 4th, as the men headed toward Sheridan’s headquarters, arriving on the morning of April 5. They soon learned that Smith’s Third Brigade was being attacked along the Amelia Springs Road south of Paineville. Smith’s brigade had struck the retreating Confederate wagon train and destroyed two hundred wagons. They were counter-attacked by General Fitz Lee’s cavalry and forced south.

Both Gregg and Davie’s brigades were sent as reinforcements. The Second Brigade faced Lee’s angry soldier’s in their attempt to rescue their fellow soldiers. They forced the enemy to fall back, but not without cost. In less than half an hour 31 men in the 21st Pennsylvania were lost and another 23 men were wounded.

Over that day and the next the battles continued as the North pressed its advantage toward the goal of destroying Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia. A large attack at Little Sailor’s Creek resulted in deadly conflict and multiple charges that resulted in the route of Confederate forces. About six thousand Confederate soldiers were captured, among them two generals.

Battles over the next several days centered at areas around Appomattox as the Union gradually succeeded in driving the southerners from the field. The 21st Pennsylvania made one of the last charges of the war when they failed to receive the order to “halt and cease firing.” The 21s Pennsylvania Cavalry charged alone against the enemy. Finally, seeing that he was unsupported by the rest of the line Colonel Knowles halted the attack when the recall was sounded. Four years of fighting had ceased. The war was over.

After the surrender at Appomattox Court House, the 21st Pennsylvania Cavalry marched to Prospect Station, Burkeville, Nottoway Court House and then back to Petersburg. While they were on this march the sad news of Lincoln’s assassination reached them.

May and June were consumed by the kinds of routine duties of an army in the process of disbanding. Daniel Oliver’s Company E spent their time as the Sixth Corps headquarters escort. Eventually the men of the 21st Pennsylvania Cavalry turned over their horses and equipment and on July 8th they were mustered out of service. The journey to Pennsylvania took a week and from Harrisburg the men were released to return home.

============================================

Organization

The original 21st Cavalry as organized at Harrisburg and Chambersburg June 28-August 1, 1863, for six months. Companies "C," "E," "H," "K," "L," "M," duty at Pottsville, Pa., and Scranton, Pa., and Company "B" at Gettysburg, Pa. Companies "A," "D," "F," "G" and "I" ordered to Harper's Ferry, W. Va., August 23, 1863. Attached to Cavalry Brigade, 1st Division, Dept. West Virginia, to February, 1864. Duty about Harper's Ferry, W. Va. Expedition from Charlestown to New Market November 15-18 (Detachment). Mount Jackson November 16. Wells' demonstration from Harper's Ferry December 10-21. Skirmish at Winchester January 3, 1864. Mustered out February 20, 1864. The 21st was organized as a 3-year unit at Harrisburg February, 1864. (Co. "D" detached April 1, 1864, and duty at Scranton, Pa., entire term.) Regiment moved to Washington, D. C., May 15, 1864, thence to Join Army Potomac in the field, arriving at Cold Harbor, Va., June 1. Attached to 2nd Brigade, 1st Division, 5th Army Corps, Army Potomac, to September, 1864. 1st Brigade, 1st Division, 5th Corps, to October, 1864. 3rd Brigade, 2nd Division, Cavalry corps, Army Potomac, to March, 1865. 2nd Brigade, 2nd Division, Cavalry Corps, to July, 1865.

Service

Battles about Cold Harbor, Va., June 1-12, 1864.

Before Petersburg June 16-18.

Siege operations against Petersburg and Richmond June 16, 1864, to April 2, 1865.

Weldon Railroad August 18-21.

Poplar Springs Church September 29-October 2.

Sent to City Point October 5 and mounted.

Boydton Plank Road, Hatcher's Run, October 27-28.

Warren's Expedition to Hicksford December 7-12.

Bellefield December 9-10.

Dabney's Mills, Hatcher's Run, February 5-7, 1865.

Appomattox Campaign March 28-April 9.

Dinwiddie C. H. March 30-31.

Five Forks April 1.

Paine's Cross Road April 5.

Sailor's Creek April 6. Appomattox C. H. April 9.

Surrender of Lee and his army.

Expedition to Danville April 23-29.

Moved to Lynchburg, Va., and duty there and in Dept. of Virginia till July.

Mustered out July 8, 1865.

Losses

Regiment lost during service 4 Officers and 80 Enlisted men killed and mortally wounded and 2 Officers and 116 Enlisted men by disease. Total 202.

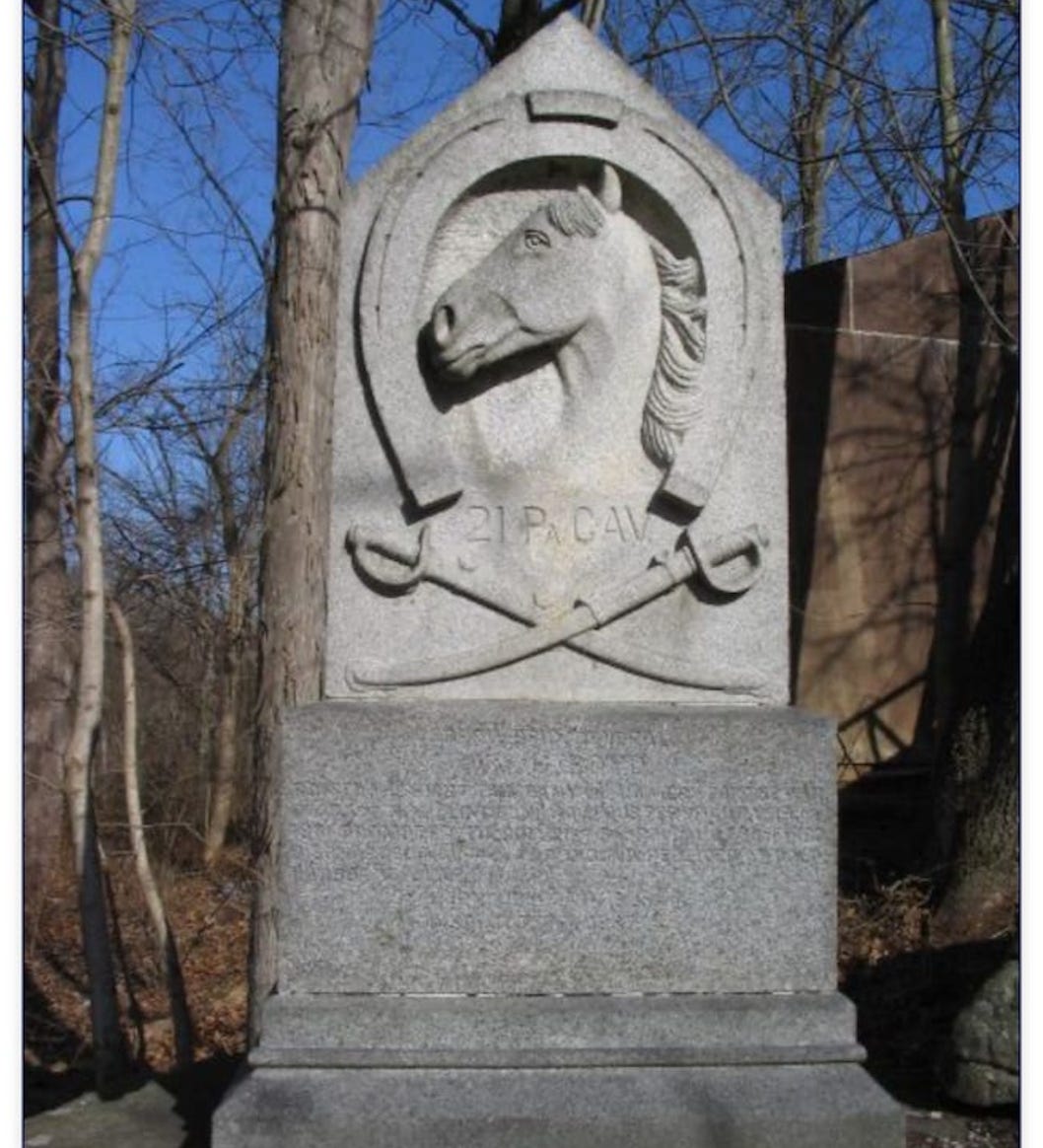

Monument to the 21st Cavalry located near Gettysburg.